When on the 18 July 1864 Joseph E. Johnston handed command of the Army of Tennessee to John Bell Hood, it numbered 64,000 effectives, 47,000 infantry including the Georgia militia, 13,000 cavalrymen and 4,000 artillerymen with 187 guns. Five months later, what remained of the army went into bivouac at Tupelo, Mississippi, south of the Tennessee River with fewer than 18,000 men, half of whom were shoeless and unarmed, possessing virtually no artillery and but a few wagons. Such was the reduced state of this gallant army after the Battles of Atlanta and the disastrous Franklin/Nashville campaign.

This paper is not concerned with the ebb and flow of those battles or of apportioning blame for the failures that befell this most noble and obstinate army. Its purpose is merely to follow the fate of the Army of Tennessee from its rout at Nashville to its last hurrah at the battle of Bentonville and finally to its eventual surrender.

The battle of Nashville was fought over two days, 15/16 December 1864 between Hood’s Army of Tennessee and General George Thomas’ Union Army. Bentonville was fought three months later on 19 March 1865 and skirmishing lasted until the 21st. Betwixt the two battles occurred one of the coldest Mississippi winters on record to that time.

At Nashville the Army of Tennessee had fought gallantly on the first day of the battle stymieing the Federal attacks of that day. On the second the 2:1 odds coupled with the superb execution of a comprehensively thought out battle plan and inexplicable, to some but entirely understandable to others, rout of the Confederate left wing that put the rebel army to flight. Federal General John M. Schofield would declare of this final fight and those that had preceded it: “I doubt if any soldiers in the world ever needed so much cumulative evidence to convince them that they were beaten.”

On the 16 December the Army of Tennessee was finally convinced. The hurried retreat soon generated into a shambolic one. General Cheatham recalled that as soon as he managed to stop one soldier and turned to another, the first would slip by him and continue on while he endeavoured to stop the other. Despite the entreaties of their officers to halt and stand the majority of surviving rebel soldiers had determined they would only do so of their own accord and that, as things turned out, was not until the Tennessee River could be placed between them and their victorious foe.

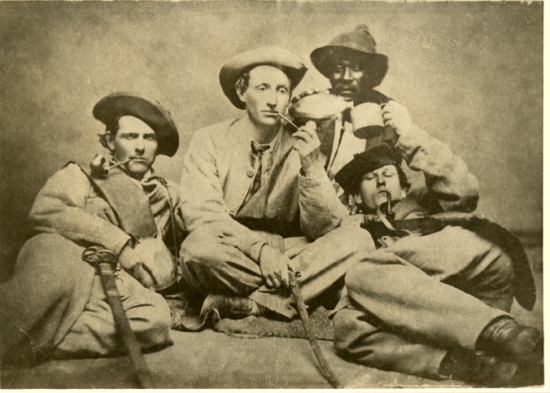

Many of the men were barefooted and left bloody footprints along the icy road. Some were still clad in summer cottons having missed the issue of winter clothing. They tried to make shoes out of coat sleeves or with any material they could lay their hands on. Some soldiers were ordered to sew beef hide into footwear placing the hair against the foot. The stench generated forced many to abandon the makeshift solution. None of these attempts were particularly effective. Blankets, too, were in short supply.

A Georgian soldier compared the army’s plight to that of Bonaparte’s retreat from Moscow and a civilian who witnessed the army passing declared it to be “the most broken down set I ever saw.”

It is interesting to consider just how ruinous campaigning was on shoes and uniforms and also how profligate soldiers could be. The Army of Tennessee had in fact received three issues of winter clothing and shoes at Gadsden, Tuscumbia and Florence, Alabama, as they prepared to march north. As well soldiers were able to load up with extra clothes and replace worn clothing from the dead at Franklin. Incidentally many Rebel soldiers considered Franklin a great Confederate victory. No such interpretation could be placed on Nashville.

After the initial rout from the Nashville battlefield some order gradually began to manifest itself and Stephen D. Lee was able to organize an effective rearguard at the Harpeth River. Outflanked he fell back to a position three miles south of Franklin and from there withdrew to Spring Hill. Undoubtedly both places elicited doleful memories for the bedraggled army.

A welcome respite was delivered when the army fell back to Rutherford Creek. The creek was swollen and the only bridge burned causing a two-day delay in the pursuit while the Yankees waited for their pontoons. Hood hoped to halt the army in the lush valley south of the Duck River but the condition of his command forced a rethink and he decided that a position beyond the Tennessee River was preferable.

The army was now fortunate to be graced by the arrival of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s command who took over the task of acting as the rearguard. Forrest had been operating near Murfreesboro and had been ordered to fall back via Shelbyville to Pulaski. In keeping with his practical approach to everything Forrest chose to take the shortest route to come to the infantry’s aid. His troopers took up positions behind the swollen waterways and soaked woodlands to slow the Federal pursuit.

Attached to Forrest’s 3,000 strong command was Walthall’s division numbering nearly 2,000 men. This was less than the strength of a single brigade within the division at the commencement of the Atlanta campaign eight months before. Like the rest of the infantry they were crippled by a lack of decent footwear and had reached a point where they simply could not march at the brisk pace required. Compounding their predicament was the loss of valuable supplies and artillery. Horse teams had broken down and many wagons and guns had been lost to the marauding Federal cavalry.

Walthall’s footsore men found themselves at a standstill south of the Duck River with a stalled wagon train crippled by a lack of horsepower. General Forrest, however, was always ready to advance a pragmatic solution in the interests of preserving his command. He ordered half the wagons to be parked and the horses from those added to the other teams. The footsore infantry was loaded into the wagons and pulled to safety further down the turnpike. Forrest then unhitched the wagons and returned with the horse teams to fetch the wagons left behind. As well, cavalrymen ferried wounded men to safety. This was concluded before the Yankee vanguard arrived.

Forrest fell back to Lynville where he launched a surprise attack on his pursuers and on Christmas Eve he engaged the Federals at Richland Creek. The army crossed the Alabama line with a last rearguard set up at Muscle Shoals. On 29 December General Thomas called off the Federal pursuit.

In five weeks the army had probably marched over 300 miles, the last fortnight being a most wretched 120-mile trek through sleet and over icy roads. Approximately 20,000 soldiers had been killed, wounded, captured or gone missing in the five weeks since Hood had struck out for middle Tennessee. Thomas recorded 13,189 prisoners and 72 artillery pieces among his captures. Among the Confederate losses was one Lieutenant General, three Major Generals, twelve Brigadier Generals and five brigade commanders of lesser rank. Only two of these were fit enough to return to active service – the rest had been killed, captured or suffered severe wounds.

The soldiers’ humour was unbowed though and as they crossed the Tennessee River the well known tune the Yellow Rose of Texas was sung with new words:

So now I’m marching southward,

My heart is full of woe;

I’m going back to Georgia

To see my Uncle Joe.

You may talk about your Beauregard

And sing of General Lee,

But the gallant Hood of Texas

Played Hell in Tennessee

One soldier declared that Hood had ‘butchered’ the army and many others were of the view that Hood was not fit for army command. One of Patrick Cleburne’s soldiers concluded “Our campaign has been the most disastrous of the war. Hood is a complete failure.”

Despite the bitterness engendered in the hearts of many, General Hood still elicited sympathy in some. One soldier seeking a furlough visited the General in his headquarters’ tent at Hollow Tree Gap by the Franklin turnpike. There he found the general weeping. He wrote: “I pitied him, poor fellow. I always loved and honoured him, and will ever revere and cherish his memory…As a soldier, he was brave, good, noble, and gallant, and fought with the ferociousness of the wounded tiger, and with the everlasting grit of the bulldog; but as a general he was a failure in every particular.”

Another soldier penned a short grim summation of the South’s plight. “Ain’t we in a hell of a fix: a one-legged general, a one-eyed President and a one horse Confederacy!” In January a returning soldier commented on a general despondency evident throughout the army, the prevailing opinion being that “the Confederacy is gone.”

The extent of the disaster to Confederate arms took time to reveal itself to authorities in Richmond. Hood sent a message on Christmas Day advising the War Department that he was laying a pontoon across the Tennessee River. This arrived on 3 January. General Beauregard as Departmental commander of the South Carolina and Georgian coast, also received a message from Hood that repeated the pontoon information and asked Beauregard to come to Tuscumbia or Bainbridge. On 3 January Beauregard arrived at Macon, Georgia and received two telegrams from Hood. One dated 17 December admitted to the loss of 50 pieces of artillery and several ordnance wagons. The loss in killed and wounded he said was very small. The other was sent from Corinth and stated the army had crossed the Tennessee without material loss since the battle in front of Nashville. A further telegram was received by the Creole as he made his way westward. In it Hood stated that the overall loss in killed, wounded and prisoners taken had not been great.

Beauregard arrived at Tupelo on 15 January. He had been authorised to remove Hood from command should he feel such a move was warranted. What he found shocked him. The army he declared was little more than an “armed mob”. He was dismayed by the extent to which Hood had deceived him in regard to the true nature of the state of the army. On reflection he magnanimously concluded that Hood’s deceit reflected a deep and personal mortification and embarrassment at the fate that had overtaken him rather than any malicious intent.

Hood requested to be relieved from command and General Richard Taylor was appointed in his place assuming command on 23 January.

The army was relatively safe at Tupelo albeit one akin to a Valley Forge experience. Other areas were considered less so and uppermost in the Confederate strategists mind was the defence of Mobile against any possible Yankee thrust. The now largely cannon less Confederate artillerymen were banded together and sent to Mobile. Stevenson’s Division from Stewart’s Corps was also despatched there for a time.

A reorganization of the army’s remnants was in order but so too was relief for the surviving soldiers. Many Tennesseans were among the ranks and close to home. Up to fifty per cent of these men received furloughs with the expectation that they would return and that when they did, they would bring new recruits from home. The Mississippians, too, were granted furloughs. In all 3,500 men were granted this welcome respite from military duties.

Needless to say many men did not return to the colours. The behaviour of many left in the ranks proved as trying for the local populace as had the Yankee marauders as hungry confederates sought to supplement their meagre rations. Hood issued orders for the summary execution of soldiers found killing livestock. Deserters and ne’er-do-wells infested the countryside and there was little local militia commanders and conscripting authorities could do to disperse these men, many of whom had set up semi permanent camps in their chosen new pastures.

The recorded strength of the Army of Tennessee on 23 January 1865 was 18,742 but from this had to be deducted the furloughed men and those despatched to Mobile, some 4,000, leaving a paltry 11,000 effectives. Forrest’s men were also despatched elsewhere as Forrest was given departmental command of Mississippi, East Louisiana and West Tennessee. The tale of woe was no better reflected than in the skeletal strengths of the ragged vermin infested regiments shivering in their encampments.

Even as Taylor was taking over the reins of the army it was being taken away from him, it having been ordered east under the nominal command of General Beauregard to reinforce the disparate Confederate forces congregating in the Carolinas to oppose Sherman.

Stephen D. Lee’s Corps, now commanded by General Stevenson, numbered only 3,078 men as it boarded the boxcars bound east. Cheatham’s Corps followed a few days later and by month’s end Stewart’s followed them.

Returning wounded soldiers reported to Montgomery from whence they were sent on to the front. Possibly the last batch to be forwarded was 500 men despatched to North Carolina on 15 April.

The route travelled was a long and indirect one fashioned by the rickety limitations of the Confederate rail system. Cheatham’s men trudged out of Tupelo to West Point where they boarded a train to Meridian and from there to Selma. At Selma they boarded steamboats to Montgomery and from there they travelled by rail to Columbus. They then marched through Macon and Milledgeville and on to Mayfield where they took trains to Augusta. They marched from Augusta to Newberry, South Carolina, where they joined with Lee’s Corps.

Discipline was lax and Granbury’s Texas Brigade formerly of Pat Cleburne’s division, according to one of its soldiers, behaved shamefully from Tupelo to Raleigh, breaking open stores and helping themselves to tobacco and liquor. That they had not been paid for ten months did not help their mood.

One thing that did improve through this generally depressing period of the army’s existence was the rations. The area that the troops passed through had been spared the ravages of war and so things such as sweet potatoes and sorghum broke the tedium of bread and meat that had formed the staple of the army’s diet while campaigning.

Mary Chestnut had witnessed Stevenson’s men swinging airily through Camden as if they “still believed the world was all on their side, and that there were no Yankee bullets for the unwary.”

By contrast, her portrait of John Bell Hood is a sobering one. Hood had stopped off at Brigadier General John S Preston’s home in South Carolina while en route to Richmond with a grandiose proposal to return to Texas and raise a force of 25,000 men to march to the aid of the teetering Confederacy. He was a suitor to Preston’s daughter Sally and her brother Willie had been killed while serving under the Texan in the Battle of Atlanta.

“He can stand well enough without his crutch.” observed Mrs Chestnut “but he does very slow walking. How plainly he spoke out those dreadful words, ‘My defeat and discomfiture. My army destroyed. My losses.’ He said he had nobody to blame but himself.”

Sally Preston’s younger brother Jack took Mary Chestnut aside and asked her. “Did you notice how he stared in the fire, and the livid spots which came out on his face, and the huge drops of perspiration that stood out on his forehead?”

“Yes, he is going over some bitter hours.’ replied the diarist. “He sees Willie Preston with his heart shot out. He feels the panic at Nashville and its shame.”

“And the dead on the battlefield at Franklin.” added Jack. “That agony in his face comes again and again. I can’t keep him out of those absent fits…When he looks in the fire and forgets me, and seems going through in his own mind the torture of the damned, I get up and come out as I did just now.”

On 23 February General Joseph E. Johnston was instructed to assume control of all troops under General Beauregard’s command with the Louisianan to act as his second-in-command. This included the Army of Tennessee now commanded by General A. P. Stewart along with Hardee’s command from Savannah, Bragg’s and Hoke’s command previously defending Wilmington plus cavalry from Wade Hampton’s command including Joe Wheeler’s men. In all, Johnston had about 21,500 men to oppose nearly 90,000 converging Yankees.

Johnston’s troops were scattered and it was thought that they could concentrate in the vicinity of Smithfield in North Carolina. At this time the Army of Tennessee was stretched across three states. Stevenson’s Corps was at Charlotte with Beauregard, Stewart’s Corps was southwest of them at Newberry, South Carolina and Cheatham’s men were strung out between Augusta and Newberry.

At Bragg’s urging Johnston attempted a pre-emptory strike against Jacob D. Cox’s corps of Schofield’s command moving up from New Bern. Two divisions of Stephen Lee’s Corps of the Army of Tennessee commanded for the moment by Daniel Harvey Hill and numbering only 3,000 men were sent by train to Bragg and Hoke who crumpled the head of Cox’s column in an attack at Kinston on 8 March 1865 and captured 1000 prisoners. Fighting erupted again two days later but the attack could not be sustained and so Bragg withdrew toward Johnston minus about 200 casualties. They had, at least, halted one of the Federal thrusts momentarily.

Johnston, now with the majority of his forces concentrated decided to ambush Sherman’s advancing army at Bentonville. The Army of Tennessee was represented by Cheatham’s Corps commanded by Major General W. B. Bate and Stewart’s Corps (Hill in command) of three divisions, Stevenson’s, Clayton’s and Hill’s (Col. J. G. Coltart in command). Walthall’s division which had fought the rearguard with Nathan Bedford Forrest’s troopers was there too numbering one hundred men led by two generals. The veterans fought bravely and on the first day carried the Federal positions before them until Yankee resistance stiffened. Skirmishes over two days showed the Federal line to be an ever expanding one and eventually Johnston was forced to concede the field.

By month’s end Johnston had received the balance of the Army of Tennessee’s depleted Corps plus several thousand other men brought up by Stephen D. Lee, who had finally recuperated from his wounds in Augusta. While there he had collected various scattered attachments into a single cohort.

Johnston commenced a reorganization of his forces. The various components would be reconstituted and unified as the Army of Tennessee again under his command. On paper it looked a potent force even if not so numerically. Hardee’s Corps comprised three divisions led by Hoke, Cheatham and John C. Brown. Stewart’s Corps’ three divisions were headed by Patton Anderson, Walthall and Loring. Stephen D Lee resumed Corps command with two divisions under Daniel Harvey Hill and Carter Stevenson.

On 26 April the Army of Tennessee was formally surrendered to General Sherman at the Bennett House near Durham Station, North Carolina. Two days beforehand Johnston reported an effective strength of 15,188 men. Final parole figures from the United States government listed the men surrendered from the Army of Tennessee and others as being 31,243.

The Army of Tennessee’s war was over.