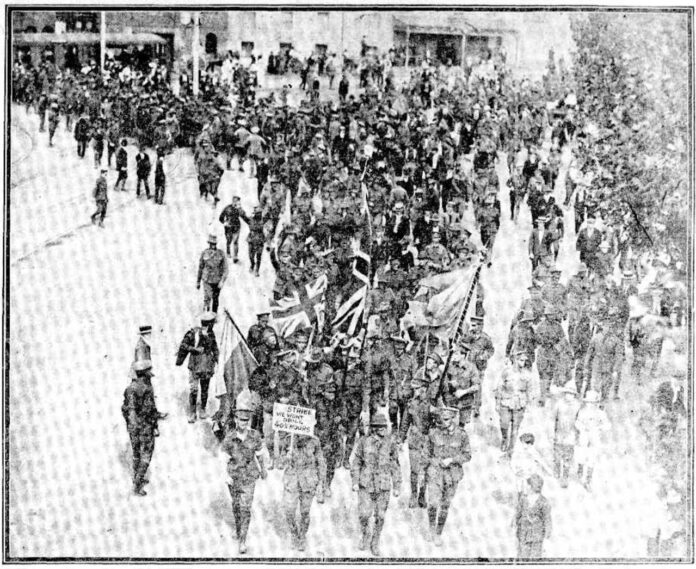

Image Source: (1916, February 15). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 – 1930), p. 7.

On St Valentine’s Day 1916 one of the worst examples of soldier unrest occurred in Australia’s military history when an estimated 10,000 volunteers took leave of their training camps at Casula and Liverpool and marched in protest through the city of Sydney. The day would end in tragedy with the death of a soldier but it was a day that also saw widespread disruption to the city’s activity and destruction to numerous properties. This mass demonstration on the part of the soldiers was variously described as a strike, a mutiny and a riot. In truth it was all of these things. It was an extraordinary and spontaneous explosion of disaffection on the part of the volunteers and one which alarmed civic leaders, military commanders and the police. This paper will examine the reasons for the soldiers’ grievances that sparked the demonstration and in doing so will show the difficulty military authorities had in expunging civilian viewpoints from the volunteers’ perspective of army life as well as revealing the extent to which views about industrial militancy were invoked to interpret the incident.

A prime function of military training, certainly in a full time army, is to establish an esprit de corps what General Carl von Clausewitz in his famous treatise On War termed as a ‘corporate spirit’.[1] This was a particular soldier identity that stressed a sense of belonging, of loyalty to unit and to comrades in arms. In his study of the combat identity of First World War soldiers, Eric Leed suggested that the transition from citizen to soldier heralded the beginning of a new identity whereby the recruit embarked on a series of initiations that marked a distinctive rite of passage. Leed contended that a soldier’s identity is both separate from his civilian identity and unique in that it is formed beyond the margins of normal society.[2] The first stage of this process – and the first act of separation – was the soldier’s entry into camp. This shift in identity seems a logical one but the transition needed time and the volunteers who crowded the camps at Casula and Liverpool were not sufficiently distanced from the margins of normal society either geographically or psychologically.

This early transition was one fraught with pitfalls and presented problems, derived from both civilian and military causes, that affected the discipline and early organisation of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). These problems were addressed by Colonel H. N. MacLaurin, commanding officer of the 1st (New South Wales) Brigade, in a confidential report on the raising and equipping of the Brigade. Many of MacLaurin’s complaints emanated from poor administrative procedures and ranged from difficulties in the acquisition and distribution of uniforms, to shortages in tents and camp equipage, to delays in pay. There was also too few qualified staff to cope with the burden of clerical work and the battalion commanding officers found themselves embroiled in a paperchase rather than giving their minds over to the practicalities of military training. By far the greatest of MacLaurin’s concerns was the closeness of the Brigade encampments – at Randwick and Kensington racecourses – to the city with its obvious distractions. He maintained that this had contributed toward many absences from the camp, undermined discipline, and contributed to the contraction of venereal disease by some of the men. The majority of NCOs responsible for enforcement of discipline among the sections and platoons were inexperienced and appointed on a provisional or temporary basis. This posed problems not only for the discharge of discipline but for the conduct of basic military drills.[3] In response to the concerns expressed by MacLaurin and others it was decided to shift the volunteer encampments to Casula and Liverpool. The camps lay twenty miles west of the city. The distance provided a useful, though not insurmountable, barrier that deterred recruits from attempting to savour the fruits of the city.

Another important aspect pertinent to the problems that arose was the make up of the men themselves. The majority of the volunteers who enlisted in the AIF were young single working class males. The pre war occupation of some 65 per cent of volunteers was blue collar.[4] Many of these men would have been trade unionists though we have no way of knowing exactly how many. Supposing half of these to have been trade union members would be a conservative estimate but one that demonstrates just what a significant representation trade unionists held among the volunteers. These men were no strangers to industrial militancy and the Trade Union’s core value of solidarity was one that was very similar in its intent to the esprit de corps that the army was trying to cultivate. A prime objective of the Australian labour movement was the introduction of a shorter working week and the eight hour working day had become sacrosanct since its introduction in the mid nineteenth century even though it was still not enjoyed by many workers outside of the unionized key industries.[5]

Central to the strife at the Casula and Liverpool camps was a decision to extend training hours but this alone was not the sole reason that triggered the protest.

Entertainment in the camp was restricted and centred on the many bands that played there. Occasionally fights among the recruits punctuated what was usually a mundane existence.[6] The boredom in the camp was exacerbated by the constant delays in embarkation dates. This often brought embarrassment to soldiers who had farewelled friends and relatives only to have to later inform them that the date of embarkation had been deferred.[7] The chief reason for such delays lay in the difficulties that the government had in acquiring transports. Apart from the boredom, many of the men harboured complaints about the conditions and their treatment at the camp.

Complaints about the Liverpool Camp predated the war and trouble was not unknown to it. Conditions were Spartan, consisting of the most rudimentary barracks and material. On 29 November 1913 a riot of sorts had broken out among Compulsory Service trainees which resulted in the matter being investigated by a court of inquiry. Of particular interest in that event was that the trouble was caused mainly by the behaviour of the 14th Battalion, a unit drawn largely from the mining town of Newcastle and districts – men not unaccustomed to militancy in the acquiring of working rights. Poorly trained men and poor officers who lacked common sense combined to cause a breakdown in discipline and inflame the trainees’ feeling of injustice when they were confined to camp while the officers, in full mess dress, readied themselves for dinner. The incident concluded with an abusive and rock throwing mob of several hundred soldiers dispersing before a resolute guard of twenty-five men standing firm at the bridge over which the men had to pass to leave the camp.[8] This disturbance served as a warning as to what might happen on a larger scale if military authorities did not adjust their attitude to the treatment and conditions of civilians undergoing military training.

The use of the camp to train volunteers also brought complaint to the floor of the New South Wales parliament. Mr R. B. Orchard, the Member for Nepean, raised criticisms of the camp, chief among them being a lack of uniforms and decent bedding, a shortage of overcoats, a lack of rifles for training and an inadequate system for the dispensing of medicines and treatment of the sick. Of particular disgust to the troops was that German internees at the internment camp, also at Liverpool, suffered none of these shortages.[9] Orchard’s criticism appears to have had a positive effect and in the inquiry that followed a number of soldiers stated that overcoats were only issued following the politician’s comments.[10]

Despite the parliamentary intervention, trouble persisted at the camps. A disturbance was reported on the night of 26 November 1915 when soldiers without leave passes attempted to pass sentries on the bridge leading out of camp. Several thousand men were drawn to the scene. Stones were thrown and three or four police tents were set alight. The incident was not considered, by the camp’s commandant, to have assumed serious proportions.[11] That the situation at Liverpool finally dissolved into a general strike (or mutiny) was hardly surprising. The action that inflamed the men’s grievances was a decision to extend training hours by four and a half hours.

The decision to lengthen training hours had followed a recommendation by Major-General McCay, who had toured the camp; it had provoked much ill-feeling among the men. Under the training syllabus extant at the time the men were required to train for thirty hours.[12] McCay’s recommendation was that training be increased by four and half hours a week. It could hardly be said that these hours were unreasonable given they fell below those that most civilians were working. Yet to those who took umbrage the increase, without compensation, was clearly seen as breaking the contract they thought they had entered into.

Trouble first began at the light horse camp at Casula, and when those men, numbering approximately 500, marched across to the infantry camp at Liverpool the number of strikers swelled to about 10,000. This mass of men marched out of the camp, and two representatives from each battalion were sent as part of a large delegation to the camp commandant Colonel Miller. Miller told the men that the matter should have been brought to him without striking; he asked that they return to work under the old hours and he would approach the state commandant to see what could be done. This was considered unsatisfactory by the men, who by this time were emotionally intoxicated by participation in such a large demonstration and they marched to the railway station at Liverpool. The cellar of the Commercial Hotel was raided and barrels of beer were rolled into the street and their contents consumed by some of the excited mob. A small force of local police was on hand but powerless to halt what was described as a ‘campaign of plunder and destruction’.[13] After indulging in such excesses throughout the township, the soldiers boarded trains to the city to air their dissatisfaction.

The city next fell victim to the soldiers’ attention. In what was described as ‘unprecedented scenes’ shops were robbed, windows smashed and motor vehicles commandeered by mobs of soldiers.[14] Particular attention was paid to the shops owned by Italians and Germans. The mayhem petered out about midnight but only after a shot from a military picket at Central Railway station put a sobering and bloody stop to the madness. One light horseman was killed, Trooper Ernest William Keefe, who was reported as being shot through the cheek and bayoneted in his left side, shoulder and neck. A post mortem revealed he had been struck by a single bullet and had no other wounds. Five other soldiers and a policeman were injured in the fray.[15]

Although reports of the episode concentrated on the destructive aspects there was also a large element of order to the soldiers’ behaviour. The march was clearly intended as a protest demonstration and, as each train arrived from Liverpool, the men were formed in column of fours and marched from the station by appointed leaders or possibly the senior NCOs in the group. The column was headed by standard bearers carrying the green and purple colours of the 2nd Battalion and a Union Jack. The core of the marchers moved in an orderly fashion; when trouble flared the leaders or sensible heads within the ranks addressed the men, appealing to their sense of fair play. This formation was loosely held during the whole of the march through the city. The unruly behaviour was caused by men on the periphery of the march and by various breakaway groups that dropped off as the march progressed.[16]

Conditions at Liverpool and Casula had certainly warranted some form of protest, but the nature of that which occurred was certainly regrettable and brought little sympathy to the volunteers. A number of letters by returned servicemen to the Sydney Morning Herald expressed disgust at the troops’ behaviour and advanced the argument that their actions let down the troops at the front. It was implied that the men at the front endured far worse conditions and would not have participated in such an action.[17]

State and unit pride were wounded in the affair. The editor of the Sydney Morning Herald believed the honour of the state had been ‘cruelly besmirched’ by an event he branded as nothing short of ‘rank mutiny’.[18] The editor of the Daily Telegraph used the affair to convey his disgust at the Labor party and trade unions, whose influence he clearly saw manifested describing it as ‘simply another and an extreme instance of the organised contempt of the law’.[19]

Serving members of the 2nd Battalion, whose colours had headed the march, and the 6th Light Horse to whom the dead soldier belonged, were chagrined by the episode. The disappointment of the Light Horse was conveyed in a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald by the unit’s chaplain. Another who wrote was an unidentified corporal of the 15th Reinforcements of the 1st Battalion. This was one of the groups that comprised half of ‘the Waratahs’ – the South Coast recruitment march volunteers. He was keen to distance his Battalion from the stigma of participation in the disturbance stating that ‘no contumely should attach to this battalion, which to a man, remained true to their King and officers’.[20]

Since it was reported widely in the newspapers, news of the strike and earlier disturbances was conveyed to the men overseas. They, like the returned soldiers in Sydney at the time, exhibited little understanding or sympathy for the soldiers’ motives. Their attitude reflected a shift in the process of separation from home and a sharpening of their soldier identity. The men overseas applied their own standards of interpretation to the events, standards acquired under quite different circumstances. Military service overseas was much more rigid in containing the movement of the troops. The soldiers in camp in Egypt and in the line in France probably regarded the troops in Australia as enjoying more freedom than they themselves were allowed. By the time the AIF had reached France the majority of the reinforcement groups in camp at the time of the strike were en route to France. Their arrival was being monitored. Captain D. V. Mulholland, of the 1st Brigade’s machine gun company, made plain his thoughts, ‘Those Liverpool rioters have arrived and are reaping their just reward. In a month’s time if they are still alive they will be very different people’.

The action of the soldiers at Liverpool/Casula and throughout their subsequent protest march through Sydney provides a clear example of how the civilian and working class values carried by volunteers into the armed services had not yet been overtaken by the more patriotic expectations of army administrators and public moralists. As the response to the strike action of some the returned men in Sydney and those serving overseas showed, that transition would be achieved in time. That said, the paradigm of industrial action was never fully eradicated from the character of the Australian volunteer and it would continue to be invoked to express numerous grievances throughout the war in most battalions.[21]

[1] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Pelican, London, 1968, pp. 254-5. It was published posthumously under its original title Vom Kriege in 1833.

[2] Eric Leed, No Man’s Land: Combat and Identity in World War I, Cambridge University Press, London, 1979, p. ***

[3] Confidential Report on the Raising and Equipping of the First Infantry Brigade, Australian Imperial Force, by Colonel MacLaurin, in 1st Brigade Diary, appendix no. 28, AWM 4.

[4] L.L. Robson, The First AIF: A Study of its Recruitment, Melbourne University Press, 1970, p. **; L. L. Robson, ‘The Origin and Chracter of the First AIF, 1914-1918: Some statistical Evidence’, Historical Studies, vol. 15, 1973, p. **

[5] For a discussion of the history of union campaigns for a shorter working week see, Rowan Cahill ‘On Winning the 40 Hour Week’ Illawarra Unity – Journal of the Illawarra Branch of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 7(1), 2007, pp. 16-25.

[6] Pte Herb Bartley, ‘First Day In Camp’, Delegate Argus, 3 June 1915.

[7] Harry Sharpe, ‘The Australian Way’, Town and Country Journal, 15 September 1915.

[8] Craig Wilcox, ‘Australia’s Citizen Army, 1889-1914’, PhD, ANU, 1993, pp. 334-7.

[9] Town and Country Journal, 7 July 1915, p. 23. For a most benign account of the men’s grievances and subsequent events see Ernest Scott, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18: Australia During the War, vol XI, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1938, pp. 228-30.

[10] A subsequent report on conditions of Liverpool Camp clearly vindicated the men’s grievances if not their actions and provided a lengthy list of recommendations to improve conditions and administration; Town and Country Journal, 28 July 1915.

[11] Town and Country Journal, 1 December 1915, p. 12.

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 February 1916.

[13] Town and Country Journal, 16 February 1916, p. 12.

[14] Daily Telegraph, 15 February 1916.

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1916; Daily Telegraph, 15 February 1916.

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1916; For fuller accounts of the disturbance see M. Darby, ‘The Liverpool-Sydney Riot’, MA Thesis, University of Western Sydney, 1997; Dale Blair, Dinkum Diggers: An Australian Battalion at War, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2001, pp. 40-44; Nathan Wise, Anzac Labour: Workplace Cultures in the Australian Imperial Force during the First World War, Palgrave MacMillan, 2014, pp. 27-30.

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 December 1916.

[18] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 February 1916.

[19] Daily Telegraph, 15 February 1916.

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February 1916.

[21] For a battalion specific example of the nature of unrest within battalion life, see the chapter “Class is Everything” pp. 37-68 and discussion of the 1st Battalion mutiny on 21 September 1918, pp. 157-164 in Blair, Dinkum Diggers. For examples throughout the AIF see Wise, Anzac Labour, passim.